SP-4223 "Before This Decade Is Out..."

[14]

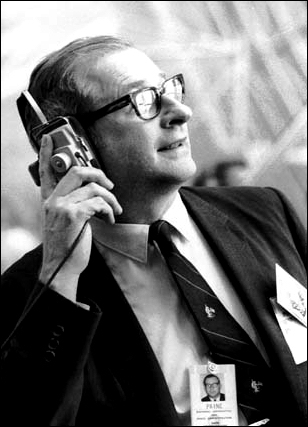

[15] Dr. Thomas O. Paine was appointed deputy administrator of NASA on January 31, 1968. Upon the retirement of James E. Webb on October 8, 1968, he was named acting administrator of NASA. He was nominated as NASA's third administrator on March 5, 1969, and confirmed by the Senate on March 20, 1969.

During his leadership, the first seven Apollo missions were flown, in which 20 astronauts orbited the Earth, 14 traveled to the Moon and four walked upon its surface. Many automated scientific and applications spacecraft were also flown in U.S. and cooperative international programs.

Paine resigned from NASA on September 15, 1970, to return to the General Electric Co. in New York City as vice president and group executive, Power Generation Group, where he remained until 1976.

Paine began his career as a research associate at Stanford University from 1947 to 1949, where he made basic studies of high-temperature alloys and liquid metals in support of naval nuclear reactor programs. He joined the General Electric (GE) Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York, in 1949 as research associate, where he initiated research programs on magnetic and composite materials. In 1951, he transferred to the Meter and Instrument Department, Lynn, [16] Massachusetts, as manager of materials development, and later as laboratory manager. Under Paine's management the laboratory received the 1956 Award for Outstanding Contribution to Industrial Science from the American Association for Advancement of Science for its work in fine-particle magnet development.

From 1958 to 1962, Paine was research associate and manager of Engineering Applications at GE's Research and Development Center in Schenectady. From 1963 to 1968, he was manager of TEMPO, GE's Center for Advanced Studies in Santa Barbara, California.

Paine's professional activities have included chairmanship of the 1962 Engineering Research Foundation-Engineers Joint Council Conference on Science and Technology for Less Developed Nations; secretary and editor of the E.J.C. Committee on the Nation's Engineering Research Needs 1965-1985; member, Advisory Committee and local chairman, Joint American Physical Society-Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers International Conference on Magnetism and Magnetic Materials; chairman, Special Task Force for U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; Advisory Board, AIME "Journal of Metals"; member, Basic Science Committee of IEEE, Research Committee of the Stanford University School of Engineering, and Board of Scientific Advisors of the Quarterly Journal "Research Policy."

Paine was born in Berkeley, California, November 9, 1921, son of Commodore and Mrs. George T. Paine, USN (Ret.). He attended public schools in various cities and graduated from Brown University in 1942 with an A.B. degree in engineering. From 1946 to 1949 Paine attended Stanford University, receiving an M.S. degree in 1947 and Ph.D. in physical metallurgy. He has received honorary doctor of science degrees from Brown University, Clarkson College of Technology, Nebraska Wesleyan University, the University of New Brunswick (Canada), Oklahoma City University, and an honorary doctor of engineering degree from Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

In World War II, he served as a submarine officer in the Pacific and in the Japanese occupation. He qualified in submarines and as a Navy deep-sea diver and was awarded the Commendation Medal and Submarine Combat Insignia with stars.

In 1985, the White House chose Thomas Paine as chair of a National Commission on Space to prepare a report on the future of [17] space exploration. Since leaving NASA 15 years earlier, Paine had been a tireless spokesman for an expansive view of what should be done in space. The Paine Commission took most of a year to prepare its report, largely because it solicited public input in hearings throughout the United States. The Commission report, Pioneering the Space Frontier, was published in a lavishly illustrated, glossy format in May 1986. It espoused "a pioneering mission for 21st-century America"-"to lead the exploration and development of the space frontier, advancing science, technology, and enterprise, and building institutions and systems that make accessible vast new resources and support human settlements beyond Earth orbit, from the highlands of the Moon to the plains of Mars." The report also contained a "Declaration for Space" that included a rationale for exploring and settling the solar system and outlined a long-range space program for the United States.

Paine was married to Barbara Helen Taunton Pearse of Perth, Western Australia. They had four children: Marguerite Ada, George Thomas, Judith Janet, and Frank Taunton. Paine died of cancer at his home in Los Angeles, California, on May 4, 1992.

[18] Editor's note: The following are edited excerpts from two separate interviews conducted with Dr. Thomas O. Paine by Robert Sherrod. Interview #1 was conducted while Dr. Paine was administrator of NASA at NASA Headquarters on August 14, 1970. Interview #2 was conducted on October 7, 1971, in New York, after Dr. Paine had left NASA to become vice president and group executive for GE's Power Generation Group.

Interview #1

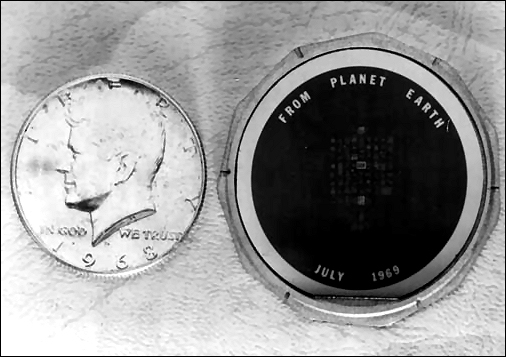

I've heard somebody say that you wanted to put a Kennedy half dollar on the Moon and it got turned down at the White House.

No, as a matter of fact that is not the kind of question that I would have raised at the White House. I did raise the question whether or not we should put a Kennedy half dollar on the Moon, and I also thought of putting one of his PT-109 tie clips, or some artifact. It seemed to me we ought to do something. And then we came around to the view that probably the best thing that we could put on the Moon as a memento of Kennedy's involvement was his statement about going to the Moon. So it got incorporated into the silicon disk,1 and, as far as I was concerned, that was a suitable way of having a piece of President Kennedy there.

Yes. That's what he'll be remembered for, I'm sure. Do you know-I think this is true-when the language of the inscription on the lunar module (LM) [plaque] was sent over to the White House (I think a word or so was changed), Nixon knocked out his middle initial? I think that's the first time he decided to drop the M from his name.

I hadn't heard that we were responsible for the disappearance of Milhous.

Somebody over at the White House told me this.

It's possible. Actually, that plaque2 -we had quite a flap over here in those final days before we had to make the decision and load the spacecraft about what we should carry. The decisions were primarily...

[19]

....by Shap [Willis H. Shapley, NASA associate deputy administrator] and myself. I remember being in Shap's office one afternoon-our shirts were open, our ties were loosened-and I remember getting a tablet and we sketched out this little plaque. And then we got the artist to draw it-well, we didn't like it this way, we didn't like it that way and we horsed around with it back and forth-and in a very short time we came up with the final thing. And the only change that was made in the White House was the change in tense. When we sent it over to the White House all finally done we had "We come in peace for all mankind" and they changed it to "We came in peace for all mankind." We were just delighted with that. That's what I call the kind of decision where you go in with some grandiose project to somebody and then try to get them arguing about whether it should be pink or green. The fact that they bought the whole thing was ideal, and we didn't care about changing the tense.

[20] The other change was that they knocked out his middle initial . . .

Certainly one thing that would make the President think about how he wanted his name to go down in posterity was the fact that we were going to put it on the Moon for all time. So I'm sure it helped him make up his mind.

I remember hearing that there was a long and hard debate about whether to go ahead with the [Apollo 13] mission. Is this true?

Not with Jim Lovell. There was no debate whatsoever. But I think it's very important in discussions like this to always make sure that you've taken enough time so that you not only go through the subject once but you go through it two or three times, asking the questions in somewhat different ways, so that if he's hesitating to bring up some subject, after awhile-you continue to dig in an informal way-if there is anything there it surfaces. And I talked to Jim long enough to completely convince myself that Jim had no reservations, that he was comfortable about this flight.

As you know, I've made it a practice to go down to the Cape and talk to the fellows before every mission in an informal way, just making sure that they don't have any possible reservation that they've hesitated to bring up with Deke [Slayton] or Chris [Kraft] or Bob Gilruth, Rocco [Petrone], Sam Phillips (in his day)- just to make sure that they know they have this channel. Nothing has ever been turned up in these meetings. I always made one other point with them, and that was to urge them to feel free at any time, if they didn't feel comfortable with the way the mission was progressing even if they couldn't put their finger on all the specifics, to feel very comfortable about aborting the mission. And I've assured them that in the event that they made a decision to bring the ship back prematurely, that if they then requested the opportunity to fly on another mission immediately afterwards-I won't say the next flight, but immediately afterwards-that I would see to it that we bent all the rules and gave them this opportunity. I wanted them to feel that if they didn't feel they were on a good mission that-but they still wanted to fly a mission-that in their ....

[21]

...own minds they would be ready and willing to turn back and we'd give them another shift. They could fly that out and they wouldn't have to go to the end of the line, they wouldn't lose their chance to go to the Moon.

Are you speaking now of before the launch or during Earth orbit or . . .

Before the launch. This is an informal thing, and has traditionally been my last statement to the astronauts. For example, I would usually go down and have dinner with them. And we talked at [22] dinner usually about other subjects, and finally got around to the mission over dessert and coffee. We usually start out with a few drinks beforehand to get everybody relaxed. And then my last statement, in private, to the three astronauts together, will be to say "I have one final statement that I want you to remember as you fly this mission," and then I would make that offer to them, that they should feel free to bring the ship back if they don't feel that they want to continue with the mission, and we'll give them another crack at it.

Did you start this with Apollo 8?

Yes.

How about Apollo 7?

I don't remember Apollo 7. I don't believe I did with Apollo 7. I believe I started with Apollo 8. Apollo 7, of course, was a somewhat different mission because once the thing was launched, you know, they could bring it back anytime, and we wouldn't want to repeat that mission anyway. The whole objective was to go there and check the spacecraft-it was a little different. But Apollo 8 and subsequently, this offer was made. Also, before I made the decision to send Apollo 8 around the Moon I called Frank Borman on the telephone and discussed it with him, as a part of the final decision process, to make sure I understood how Frank felt about it.

. . .Do you ever recall using the LM as a lifeboat-being apprised of that use of the LM as a lifeboat-during the whole Apollo 8 discussion?

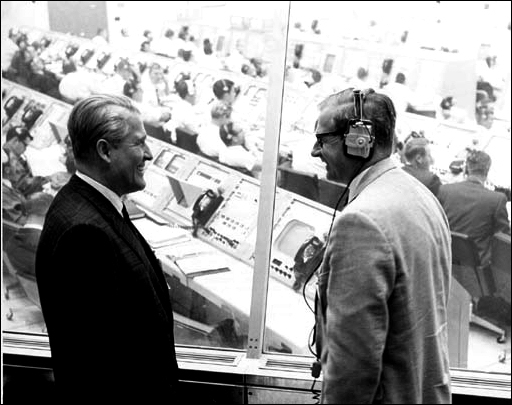

The fact of the matter is that the whole reason for sending Apollo 8 around the Moon was because the LM wasn't ready. And this was the thing which came out in August while George Mueller and Jim Webb were overseas. The question that came up was that all of a sudden-and this has always seemed very mysterious to George-the LM schedule suddenly slipped a couple of months the minute he [23] left the country . . . As soon as they got over the Atlantic, the LM schedule was re-examined and found to be a couple of months late. Then the question came up what should we do? Should we postpone the next Saturn V launch and move it on out until the LM was available and go ahead and fly the mission (which we subsequently flew as Apollo 9, the Earth orbital LM mission). Now, from the standpoint of nicety, I think you could make a very good case that, yeah, the first thing to do is fly the LM in Earth orbit before you send it out to the Moon, and then send the two out to the Moon as we did in Apollo 10. But it wasn't-there was no question from the beginning of that decision about having a LM along, and the whole reason we were going out to the Moon is because we didn't have a LM. And the discussion was-we did raise the discussion-to what degree does this increase the risk of going to the Moon? And one of the things we had to look at was the fact that, well, if we had a LM along as we would in later missions, we would have a return capability. This was partly offset by the fact that we were going to fly a free-return trajectory, so it was only when we dropped into lunar orbit that we would lose this-we would be back to the single-point failure. On the other hand, once we dropped into the lunar orbit on a regular Apollo flight we also lost the LM, you see. So in looking at it, the only time that the LM would have helped you was in the time that we had the failure in Apollo 13 on the long coast out to the Moon. And this was a risk that we just plain tried to assess and decide whether or not to fly; we decided to accept that risk.

I can't find anywhere that anybody ever said, my God, if we fly this Apollo 8 without a LM we are going to lose the lifeboat capability.

I do recall the subject coming up but I can't remember when, it may have been as early as August [1968] or in some later discussion. But it wasn't given much, we certainly didn't put much on it. And the reason was that we only envisioned the lifeboat as being a viable thing in that relatively brief period on the trans-lunar injection and subsequent coast.

Now I think the other comment you have to make is what were the things that really concerned us. Things that really bothered [24] us were things like the fuel cells. We were very concerned about what would happen if we lost power at various stages en route. And the other thing that bothered us was the life support system. What would happen if we lost oxygen and so forth? I think the other point is that during the Apollo 9 mission we did fly the lifeboat mode to check out the LM and make sure that with the two spacecraft mated that there would be no unforeseen vibration, torsion, or other problems that would occur while using the descent engine in that configuration. The one configuration we'd never flown before was the configuration that we had in Apollo 13 just before reentry, where we undocked the LM and then we undocked the service module and for awhile, we had the LM attached to the command module. That was a mode we had not flown before and there was some concern.

Have you thought about the Life contract in its origins? If you had it to do over again . . . do you think you'd do it as it was done then?

I certainly don't think I would do it again. I think that it was not a good move to make, more on principle than on anything else. Now I did look back recently and asked the question and worked with Julian Scheer [NASA's public information officer] to see if we could, in a dispassionate way, ask ourselves has this hurt the agency. And I think if you look at it dispassionately, you have to concede that it did not hurt the agency. Now, God knows there was a tremendous amount of complaint . . . It's been very annoying for us. And an awful lot of the other media people have been most upset and have complained about it. I think looking back on it, what they really sold was their byline in the family stories, and as far as NASA was concerned, what happened was that we got top billing in Life magazine on this. And I think Life is so much the standard for this sort of thing . . . it was really the leading publication, and I don't think we could have gotten a better shake. And when I look at what all the other people did to cover the program, you can't show that any daily or any weekly didn't give us absolutely full coverage. They couldn't have a byline from the astronauts but look at what all the picture magazines have done [25] with our pictures. I think they're terrific. I think you have to honestly say that it hasn't hurt the agency. But I must also tell you that I would never have signed such a contract, on the principle that I don't think government employees, who are paid by the public, should have done this . . .

Interview #2

Among the procurements made for Apollo, looking back, were there any times you thought a mistake was made . . . when you thought to override the system?

. . . The only one that I think I ever called wrong was the one that was the most logical one we ever called. It was Boeing and General Motors-who came in with the lunar rover contract against Bendix. By God, we went through that competition and everything said that it should go to Boeing and General Motors. They had done everything-lower price, everything pointed to it-and I knew damn well it wasn't right. I knew damn well Bendix was a better outfit and that it would stay within the price and would give us a better product . . . We had all kinds of cost overruns. We finally had to take it away from the Boeing crew that had it and have Boeing send in a whole new crew. All the things that we knew were going to happen at the management level did happen and yet it was too big a move to override it. Everything pointed to giving it to the people that we gave it to. It would have had to be almost an illogical act [to give the contract to Bendix] and yet the system produced the wrong answer . . .

I bet you were very glad to see the lunar rover work as well as it did.

I sure was. I was scared to death of that contract. As I said, I think that was the worst contract that I was ever in on. That was the one decision that I would have reversed if I had a bit of hindsight. I was awfully glad that thing worked. I was scared to death it wasn't [26] going to work. If that thing hadn't worked, with the TV camera on it and in front of the whole world-if it had just sat there [on the Moon] after all we'd done to take it there-it would have been a fiasco, a terrible fiasco.

Interview #1

What were the circumstances behind your resignation?

I had a fellow come in from another company-Xerox, as a matter of fact-and say that they had a high-level opening and that they wanted to know would I be interested in leaving Washington. It was a pretty good job, although I wasn't really interested in it. While-I always make it a practice never to turn anybody down, [but tell them I'll] think about it for a few days-and while I was thinking about it I ran into one of my old friends from GE and he asked me was there any possibility of my leaving, and I said no, that I was pretty well set, except that somebody had made me an offer. Sort of like a girl with a new hat, you know-it makes you feel good inside, makes you pleased even if it isn't a good one-you are reassured that you are still respected. And he said, gee, as a matter of fact they were thinking of some fairly major reorganization at GE and before I took any other offer they certainly hoped I would re-contact them. And I made my classic statement that, I really didn't think I would ever go back to GE; I'd probably want to do an independent company presidency and I really didn't think they would have anything that would interest me. Apparently it made an impression on them, because they came back shortly thereafter and said, "Look, we really don't want you to go anywhere else, we really want you to come back, we're short of top management people, and in your age bracket and experience there almost isn't anybody, and you would certainly be in a very good position, and we think we could give you a job that would give you some national problems that would have public interest associated with them and at the same time pay you a good salary." So I said, "I don't think I'd be interested but make me an offer." And as I thought [27] about it, more and more it seemed to me-as I said to the president-that maybe this was a good time for a transition here at NASA. I mulled it over for a couple of weeks, and then that Saturday before the announcement decided that I would indeed go ahead with it. One of the things I've learned from Julian Scheer is that the only way to keep it a secret is to tell everybody, and then you never get your secrets divulged because you essentially don't have any. And it seemed to me that I should do this. I talked to the president of GE about this, Fred Borch, and he agreed that although at his end he still hadn't talked to the people who would be affected and who would be essentially replaced when I showed up, that he agreed that it would be a damn good thing for me not to be in a position of having accepted an offer from him and then keeping it to myself. He said "Why don't you just get it out right away but don't say what you're going to do here?" So on that basis we did it, and I went ahead on Saturday-as soon as I made the decision-I went ahead and called the White House (the President was out in San Clemente) and said I wanted to see him Monday or Tuesday. I then called a small group of people here in the office Sunday and said, "We've got a lot of work to do: we've got to announce my resignation, I want to do it properly and I want to send out a good letter to people in NASA telling them why I'm doing it; I want to notify the people in Congress and I want to notify top executives here . . . ."

George Low didn't know?

No, and I debated that. I talked to George [Low] Saturday, right after I made the decision, and George was just leaving and he was full of his trip. And I decided, gee, George isn't going to do anything about this anyway. If I tell him, instead of enjoying his trip up from Houston he's going to be thinking about nothing but this all the way, and I thought why don't I wait and I'll let him know just before I see the president? Normally I wouldn't do that, but this was such a special circumstance, and there wasn't anything he could do about it. So I did tell him, "George, I want you to call in at noontime every day, then in the evening when you find a place [28] to stay call the NASA operators and tell them where you're staying," I said, "because there is something I'm going to want to tell you while you're en route." And George afterwards told me, "When you said that, Tom, my guess was that you were going to announce your resignation." [Laughs.] So I thought that was pretty good of George.

He had some warning after all.

Yes.

How much do you think your two-and-a-half years of government service have cost you?

Well, it's a hard question to answer because you have to ask what I would have done and how that would have come out. My guess is it hasn't cost me anything . . . I think you have to ask yourself the question "what really could you have done better with your life?" And the answer to that has to be "absolutely nothing." This has been a wonderful opportunity to work with a bunch of great people. I remember when I first got the job as a deputy-way back, even before I reported to Washington-Bill Pickering called me on the phone and said, "Gee, you know I'd like to get to know you, and once you get East you're going to be pretty busy. Why don't you come down and spend a day at the lab before you go back there?" And I said, "Gee, I'd like to do that." He said "I tell you what: we'll take you out to Goldstone and let you look around." And Barbara [Paine's wife] said she wanted to go too, and he said fine. So Bill sent a little light plane up and we flew out to Goldstone. On the way we stopped at Edwards and we stooged around the hangars and talked to the fellows there. They were a fascinating bunch of people, and the old B-70 was coming in and making some touch-and-go landings (that's a pretty spectacular thing to watch) and everybody was wearing informal clothes and really fascinated by what they were doing. And we went out to Goldstone . . . We got back and Barbara, I remember, was absolutely ecstatic, and she said "I've been there before: these are [29] all the young people we worked with during the war," she said. "These are the RAF types who have just come back from battling the Luftwaffe, these are the young submariners in Perth, this bunch of real selfless people that are doing what they want to do and taking risks and fighting odds and really doing exciting things." It was absolutely true. I think for me this has been a great recharging of my battery, and people talk about the awesome responsibility. God knows it's there-it gnaws at you all the time, there are nights when you don't sleep. I think there are very few jobs in the country-certainly none that I know of outside the military, and really not many there even-where a guy has to so put his neck on the guillotine, in the full view of the entire world, for the prestige of the country and the fates of some good people, and the professional qualifications of hundreds of thousands of people all laid on the line.

I've heard that you were vice chairman of the Scientists Against Goldwater in 1964.

That's not quite right. I had never been particularly active politically any place I'd lived, and my registration had normally been whatever I thought was the best local party and whoever I thought really in my vote might count for the most in the primary . . . When we lived in Massachusetts I actually registered Republican one year when Ike was running against Taft for the nomination, because I was so anxious to have Ike nominated instead of Taft and move the Republican Party over to a more liberal stance. Normally, I've always registered as a Democrat, and have considered myself a Democrat except for that one registration as a Republican to vote against Taft.

When the campaign came out in '64, where Goldwater was running against Johnson-like many other people who were associated with science-I became very concerned about the casual way that Goldwater was talking about the use of nuclear weapons. Really that was the one thing (I didn't really approve of his conservative position, but I wouldn't have bothered to oppose him except by my vote-except for this rather emotional issue which [30] got raised with respect to nuclear weapons). I organized, and was the chairman of the Santa Barbara Chapter of the Scientists and Engineers for Johnson. It was a one-man effort. We rented an office and we got a dozen people or so to go around and write letters asking for contributions. We took the money that was contributed and ran ads in the newspaper in Santa Barbara saying it was important not to drop nuclear weapons indiscriminately. It was a pretty casual thing . . .

He's [Goldwater] a great guy. I like him and I have great respect for him. He's a man of principle, and I think I was perhaps a little swept away, but that is such a basic issue-I just didn't think as a citizen who knew about the power of nuclear weapons I could sit on the sidelines while this sort of thing went on. But personally I like Barry-he's a great guy and he's been very good for the space program.

Did Johnson ever recall after you came to NASA that you had been chairman of the Santa Barbara . . .

No, he never knew anything about it. It was strictly a local Santa Barbara thing.

Interview #2

One thing that struck me was that, unlike Jim Webb, who had his Senator Mondale and his Congressman Ryan and his George Mueller and many others, I can't find that you really made any enemies during your time there [as NASA administrator].

I didn't make many enemies, I don't believe, but this was partly due to the time. I think given a little more time I certainly could have and would have, but NASA was going through its very greatest testing and greatest trial, and at a time like this everybody was getting aboard the bandwagon.

How did you decide on George Low for deputy [administrator of NASA]?

Basically it involved canvassing the whole country. I looked in universities, I looked in industry and I looked within NASA for candidates, and we compiled a fairly extensive list of candidates. And frankly, I must also state that one of the things in my mind was the fact that I was a bird of passage in the Nixon administration and I would be leaving one of these days-although I didn't realize how soon it would be-and I was very anxious to get somebody in who was fully qualified to run the agency in my absence, and also somebody who would give the president wide latitude in his choice of a successor. It seemed to me that while we were trying to finish up the Apollo Moon landings that having a person like myself in with a strong technical background and a person who'd exercised technical judgement over many years in a wide variety of areas . . . that this was a damn good thing to have to make that Apollo Program come out right . . . It seemed to me that whoever we put in as Deputy should leave the president the option of putting another Jim Webb kind of guy in as administrator, which I think is a good combination to run the agency.

The other criterion I put on it was I was very anxious to get a younger man. I had a feeling that when you give a person in his 40s an opportunity to run something like NASA you really bring out the best in NASA and you bring out the best in the guy. If you go and get a retired fellow who is in his 60s or late 50s, and ask him to do it, well, he's already got his reputation made and all he can do is lose and so he's going to be a little too cautious. He's not going to work the hours, he's not going to have the drive, the adventuresomeness, it won't be such a big thing to him. I was most anxious to get somebody preferably in his younger 40s but certainly no older than his late 40s. And that cut out a lot of very talented people . . . I looked at people, for example, like Frank Borman, who I felt would have in many ways been a good deputy. I looked at people like Sam Phillips. I felt it would be a damn good idea not [32] to get a military man. It seemed to me that although we had to get along very closely with the Pentagon, the president ought to keep the separation between NASA and the Pentagon-we ought to be the peaceful guys and they ought to be the military guys-and not mix them up. We shouldn't be a paramilitary organization. As far as Frank went-I thought Frank would be wonderful as maybe even the administrator, the Mr. Outside, the Jim Webb if you like-but it seemed to me that as deputy you really wanted a guy who could run the thing, although I certainly toyed with the idea of Frank and felt that in many ways he would have been a darn good choice, particularly if I were to stay on as administrator indefinitely. I felt that would be a good combination, but that probably in the long run it ought to be the other way around-the deputy ought to be Mr. Inside-a guy with a high technical competence-and the Administrator ought to be Mr. Outside, the fellow who goes to the Washington dinners and the White House and so forth, and that really you could make a better case almost for Frank in that role than you could as deputy. And I talked to various people about their interest, and I also looked very carefully among the top scientists of the nation and actually approached a couple of people like Charlie Townes3 and asked them whether they would be willing to come in, because I felt that the other way you could run the agency would be to have a fellow like myself, who of course you could replace with another guy like me in the administrator job, and get a real top scientist in, a Nobel Prize winner, as the deputy, and assure yourself then that the program really is oriented to science to a great degree.

What did Townes say?

Charlie is having too fine a time out at Berkeley and wasn't about to make the move. And I can understand that. Charlie, again, was not ideal, though. He was a little older than I'd like to have seen, he'd kind of made his reputation. It had a little bit the gloss of a circus thing. On balance, after thinking it over, talking to a number of people, I finally reached the judgment that George Low really was the ideal choice.

[33]

Did you consider Frank Borman long enough to talk it over with him?

I certainly considered him long enough to talk it over with him, but I did not talk it over with him as I recall.

I just wondered what he said. You waited a long time. You waited six months to pick a deputy.

Yes, I did. That partly reflects the fact that I wanted to get a very good candidate because I knew when I went over to the White House this appointment, which is a presidential appointment, would have to be looked at very carefully. And I didn't want any premature moves there. I wanted to have somebody that I'd fight and bleed and die for. I don't believe in losing battles.

[34] I heard there were some people in the White House who said, "Well, who is George Low? Whoever heard of George Low?"

Well, I certainly had to sell him to Peter Flanigan [an assistant to President Nixon] and to Lee DuBridge [President's Nixon's science advisor]. Lee, of course, would like to have seen a prominent scientist. Peter Flanigan, I think, wanted to assure himself that this was indeed going to be a good appointment by the president.

Interview #2

. . .It seems to me that during your career at NASA-you can correct me on any of this-the highlights of your administration, insofar as you were personally concerned or as far as the outside world, were the C Prime Decision [Apollo 8], Apollo 13, and then the fact itself of the lunar landing with the Abernathy incident.4 What else would you put in there?

Well that's a hard question. There are an awful lot of things. Of course there are a lot of things that you don't really see with much prominence that nevertheless are fairly important. I think that at the end of my regime there were some things that had to be done that I would put fairly high on my list. First of all, there was the business of getting through the transition to the Nixon administration and somehow capturing the Nixon administration for space. Nixon had made some very negative statements about space, and I think he had always associated it with his arch-rival Jack Kennedy. Getting us through that transition and getting a fairly solid base in the new administration, I felt, was one of the very great challenges . . . Having Frank Borman closely associated with the president was quite a help during this period. Bringing George Low aboard gave me the ability, then, to turn NASA over to whoever would be the next administrator knowing that we had some good solid technical competence at the top level, and that no matter who the president put in alongside, even a politician with very little background, that NASA would still have the right kind of advice at the top.

[35] Working within the new administration to get the new science adviser, Lee DuBridge, and the new secretary of the Air Force, Dr. Seamans, all pulling together to give us the role we needed through the Space Task Group and then defining for the president a good solid Nixon space program and get him to come out and publicly espouse it while at the same time sell it to the Democrats who were running the Congress-these were all great challenges.

. . . Then we had to preserve the Skylab program when it was being threatened by the Air Force's MOL [Manned Orbiting Laboratory] program.5 To thread our way through that whole period was a very tricky thing. It took an awful lot of thought, patience, and doing, along with moments of wondering whether or not we were going to pull it off.

Who talked Nixon into killing MOL . . . did you?

No. I had to, of course, play that very straight. I couldn't be a double agent who, on the one hand, would publicly advocate continuing the program but privately would try to kill it. At the same time, I was absolutely determined that if one of those programs survived-and I was damn sure that only one would survive-I wanted it to be the Skylab. I was very anxious that this be done for a number of reasons. I thought the nation would get more out of it, and I looked forward to a Soviet/U.S. cooperation in this era if we went ahead with Skylab.... I thought [it] would turn out to be exactly the opposite-a rather pernicious competition-if it went the other way. It seemed to me that an awful lot was riding on it. Furthermore, it was a program that I thought would have enormous interest in the post-Apollo area. Once we'd been to the Moon, then it seemed to me probably the first thing we'd occupy was orbital space, and that we needed a sort of transition: let us have a program there that would attract the public's interest . . . There were a lot of considerations and a lot of things to work around in that period. Not least of which, of course, was keeping the U.S. manned space effort going.

. . . There were other problems in between, such as the care and feeding of astronauts, the ability to handle a very delicate [36] public relations program with Julian having to say no to a lot of people and make a lot of enemies, which is a very useful thing for an administrator to have somebody like that who is willing to take the negative side of things and keep the administrator from having to be the heavy character . . . I well remember when I first came aboard and went down for my first launch at the Cape-the first big launch, which was the Apollo 6, the last of the unmanned launches in the Apollo Program. The air of animosity and the frank feeling I got from the reporters that the best story they could possibly get would be to have the damn thing explode on the pad the next day, in which case they would have credit lines on the front page, whereas if the damn thing went up, well there wasn't much of a story in that. And they also knew that we didn't know what the hell we were doing and that we were a bunch of bums and that it was all a great facade really-the relations with the press were not good when I first started out.

END NOTES

1. A small disc carrying statements by Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon and messages of goodwill from leaders of 73 countries around the world was carried aloft by the Apollo 11 crew and left on the surface of the Moon. The disc also carried a listing of the leadership of the Congress in 1969 and a listing of members of the four committees of the House and Senate responsible for NASA legislation. In addition, the names of NASA's top management, including past administrators and deputy administrators along with the present NASA management [as of 1969] was included. The disc, about the size of a 50-cent piece, is made of silicon. Through a process used to make microminiature electronic circuits, the statements, messages, and names were etched on the gray-colored disc. The messages were first photographed and the photo reduced 200 times to a size much smaller than the head of a pin (0.0425 x 0.055 inches). The resulting image was transferred to glass which was used as a mask through which ultra-violet light was beamed onto a photo-sensitive film on the silicon disc. After a photodevelopment step, the disc was washed with hydroflouric acid which accomplished the final etching which appears on the disc as a barely visible dot. NASA's Electronics Research Center at Cambridge, MA, was assisted by Sprague Electric Company's Semi-Conductor Division, Worcester, MA, in preparing the disc. At the top of the disc is the inscription: "Goodwill messages from around the world brought to the Moon by the astronauts of Apollo 11." Around the [37] rim is the statement: "From Planet Earth - July 1969." The messages from foreign leaders congratulate the United States and its astronauts and also express hope for peace to all nations of the world. Some are handwritten, others typed, and many are in native language. A highly decorative message from the Vatican was signed by Pope Paul. Silicon was chosen to bear the miniaturized messages because of its ability to withstand the extreme temperatures of the Moon which range from 250 degrees to minus 280 Fahrenheit. The disc itself is fragile and was transported to the Moon by the astronauts in an aluminum capsule where it remains on the lunar surface today. The words on the disc, although not visible to the naked eye, remain readable through a microscope. "Apollo 11 Goodwill Messages," NASA News Release No. 69-83F, July 13, 1969, pp. 1-4.

2. Beginning with Apollo 11, each crew carried to the lunar surface a small commemorative plaque attached to the ladder of the landing gear strut on the lunar module descent stage between the third and fourth ladder rungs from the bottom. The Apollo 11 plaque was signed by President Nixon and the three Apollo 11 astronauts. It bears the images of the two hemispheres of the Earth and the following inscription:

The plaque is made of #304 stainless steel measuring nine by seven and five-eighths inches and one-sixteenth inch thick. It weighs approximately one pound and thirteen and seven-eighths ounces. The finish has the appearance of brushed chrome and the world map, message, and signatures are in black epoxy which fills the etched inscriptions. To fit properly around but not touching the landing gear strut and to allow room for the insulation material which covers much of the lunar module, the plaque was bent around a four-inch radius. Covering the plaque during flight is a thin sheet of stainless steel which was removed by Armstrong during EVA activities on the Moon. The plaque was made at NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center. "Apollo 11 Flags," NASA News Release No. 69-83E, July 3, 1969, pp. 1-4.

An alternate account of the origins of the commemorative plaque is given by Jack A. Kinzler, a model maker and engineer who worked at the Johnson Space Center during this period. In an interview conducted with Kinzler on April 27, 1999, by the Johnson Space Center Oral History Project, Kinzler describes how he developed the idea of the plaque, produced the prototypes, and delivered the finished product at the Johnson Space Center.

In response to a high level meeting at JSC, Center Director Bob Gilruth phoned Kinzler asking him for ideas on how best to celebrate the first lunar landing. Kinzler responded with the idea of a stainless steel plaque that could be attached to the LM. Prototypes were made by both Kinzler and co-worker David L. McCraw and carried over to the meeting for approval. Everyone liked the idea and Kinzler was given the go ahead to refine the prototype into a finished product.

[38] According to Kinzler, "the first conceptual metal plaque that I took into the meeting had the American flag engraved in the middle and it was painted with red, white, and blue paints that were baked into the etched definition. It then had a place for a message, the name of the landing spot, and crew signatures." Gilruth looked at the plaque and suggested to Kinzler that they remove the flag and replace it with the two hemispheres of the Earth, one representing the Eastern Hemisphere and the other representing the Western. Kinzler went on to explain that Gilruth said "If we do that, any creatures that come in future years and look at the lunar module that's sitting there on the surface will recognize the source from where this device came."

"Once the plaque concept was approved," Kinzler said, "NASA Headquarters took it over and said 'We'd better go by the President and see if he approves this sort of thing.'" President Nixon liked the idea and wanted his signature to be included on the plaque. "NASA called down to us," and said, "we have this picture you're going to use to create your final metal plaque. Can you add the President's signatures to it?" Kinzler replied, "Yes, but we need a faxed copy of his signature." So Headquarters sent a copy of his signature to JSC. Jack Kinzler's secretary, a Mrs. Germany, saw the faxed signature that was sent to his office and pointed out that it did not look correct. According to Kinzler, Mrs. Germany's mother-in-law received a letter at that time congratulating her on her reaching her 100th birthday. The letter was signed by President Nixon but his signature did not include his middle initial "M" which was included in the faxed signature. After carefully comparing the two signatures, Kinzler decided to call NASA Headquarters to try and confirm which one they should use on the plaque. Headquarters agreed that he should use the more recent signature and, as a result, the one used on the plaque is that copied from Mrs. Germany's mother-in-law's letter received from the President. (Source: Jack A. Kinzler interview conducted for the NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project at JSC on April 27, 1999 by Roy Neal.)

Julian Scheer, assistant administrator of public affairs for NASA from 1962-1971, offers additional details concerning the wording of the lunar plaque. According to Scheer, President Nixon insisted on making a change to the original plaque wording which read "We Came in Peace for All Mankind." The President wanted to insert "Under God" after the word "Peace." However, because the timing of the change had come so late after the plaque had been installed on the spacecraft, the requested change could not be made and the original wording of the plaque, to this day, remains on the lunar surface. (Source: "What President Nixon Didn't Know" by Julian Scheer, an online article that appeared on July 16, 1999, as a special to space.com at URL http://www.space.com/news/a11plaque.html) [link no longer valid, Chris Gamble, html editor]

3. Charles H. Townes was trained in physics at Duke University and specialized in the development of laser and maser technology. He first worked for the Bell Telephone Laboratories and, in 1948, joined the faculty of Columbia University, leaving there in 1961 to move to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and on to the University of California. For his work on the maser, Townes received the Nobel Prize in 1964. See David E. Newton, "Charles H. Townes," in Emily J. McMurray, ed., Notable Twentieth-Century Scientists (New York: Gale Research Inc., 1995), pp. 2042-44.

[39] 4. Prior to the launch of Apollo 11, a large group of the "Poor People's Campaign," accompanied by muledrawn wagon, approached the Kennedy Space Center led by the Reverend Ralph Abernathy and Hosea Williams of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The marchers stopped at the visitors center where the reverend intended to protest the launch, feeling that the money used to finance space exploration should go to the poor. Paine and Julian Scheer, NASA's public information officer, met the demonstrators. Seeking to extinguish a potential PR nightmare, Paine explained to Abernathy's group that he was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and sympathetic with the poor, but stopping the launch would not put money in their hands. Paine offered to admit a delegation to observe the launch. NASA stationed buses in Cocoa, 15 miles away, to pick up the delegation and placed food packets on the seats. When Apollo 11 launched the next morning, 100 men, women, and children of the "Poor People's Campaign" were among the guests watching the spectacle. Even Abernathy was briefly overcome by emotion when interviewed on television. Paine's timely intervention helped relieve a delicate situation. Gordon L. Harris, Selling Uncle Sam (New York: Exposition Press,1976), pp. 110-111.

5. MOL (Manned Orbiting Laboratory) was a USAF manned space program that originated in the early 1960s in response to maintaining the ultimate "high ground" for military interest. As envisioned, the Earth orbiting station would accommodate a crew of two along with an attached modified Gemini spacecraft and retrofire package for ascent and reentry. The Gemini/MOL stack would be launched manned into orbit aloft a Titan III-M booster where crews would work in a shirt-sleeve environment of either nitrogen and oxygen or helium and oxygen. Designers planned to use fuel cells developed for Gemini and Apollo that would allow crews to work a 30-day mission, while longer stays would have been powered either by solar panels or thermoelectric radioisotope generators. Planned experiments performed aboard MOL ranged the gamut from military reconnaissance using large optical cameras and side-looking radar through interception and inspection of satellites, to exploring the usefulness of man in space and tests of Manned Maneuvering Units. At the end of each MOL mission, crews would climb aboard the attached Gemini through the use of a unique rear entry hatch. The retrofire package would then send the crew back to splashdown on Earth. On June 10, 1969, the MOL program was officially cancelled. Many of the reconnaissance systems ended up in later KH series satellites, while some of the manned experiments were accomplished on Skylab. Donald Pealer, "Manned Orbiting Laboratory-Part 1," Quest Vol. 4 No. 2 1995, pp. 4-16.