Prelude

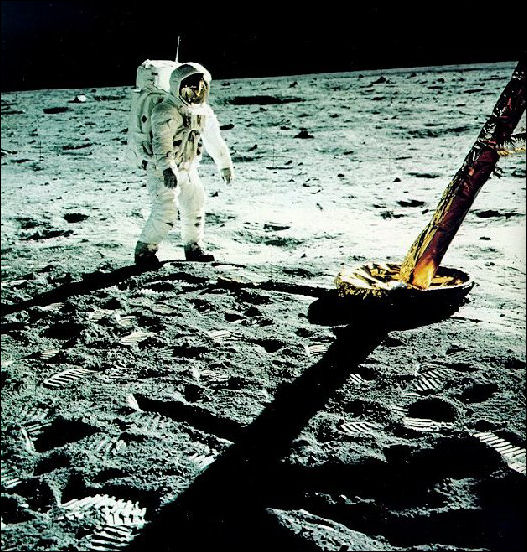

All was ready. Everything had been done. Projects Mercury

and Gemini. Seven years of Project Apollo. The work of more than

300,000 Americans. Six previous unmanned and manned Apollo

flights. Planning, testing, analyzing, training. The time had

come.

We had a great deal of confidence. We had confidence in our

hardware: the Saturn rocket, the command module, and the lunar

module. All flight segments had been flown on the earlier Apollo

fights with the exception of the descent to and the accent from

the Moon's surface and, of course, the exploration work on the

surface. These portions were far from trivial, however, and we

had concentrated our training on them. Months of simulation with

our colleagues in the Mission Control Center had convinced us

that they were ready.

Although confident, we were certainly not overconfident. In

research and in exploration, the unexpected is always expected.

We were not overly concerned with our safety, but we would not be

surprised if a malfunction or an unforeseen occurrence prevented

a successful lunar landing.

As we ascended in the elevator to the top of the Saturn on

the morning of July 16, 1969, we knew that hundreds of thousands

of Americans had given their best effort to give us this chance.

Now it was time for us to give our best.

|